Text: Tsuyoshi Yamashita

Yoshimasa Sugawara is an amazing rally driver. It is a tremendous feat each year simply to enter the Dakar Rally, the world's toughest, which runs through 10,000 kilometers of wilderness and desert over about two weeks. Maintaining this effort for over 30 years without interruption is superhuman, but even more surprising is the fact that Sugawara has now reached the age of 77. When asked about the Dakar Rally, Sugawara responded in this way. "The goal is the start"

What does this mean? From the instant each rally ends safely, goal achieved, he starts preparing for the next rally. For Sugawara, his entire year is centered around the rally

“When you've made it to the start line, the rally is almost over. Running the race itself is almost like an epilogue. There’s no point if your efforts kick in only from the start line.”The words resonate with meaning because of who speaks them—Yoshimasa Sugawara, who holds the record for 36 consecutive entries in the Dakar Rally. Perhaps this is simply Sugawara's ingrained habit. From an early age, he has won success by doing what others avoid, confronting things difficult to achieve, and challenging himself over and over again.

This success must have been a formative experience for Sugawara. At the time, he was 6 years old. He had learned that despite seeming impossibility, building up incremental efforts without rushing toward the end result leads to success.

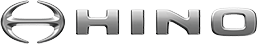

"I was absorbed in playing by myself, because I was an only child, but my father's influence was also significant."Sugawara's father had a true gift for business—he worked as a coal miner, municipal rail driver, prison officer, and police officer, and after the war he established a soap factory and made his fortune, then turned to the financial industry.

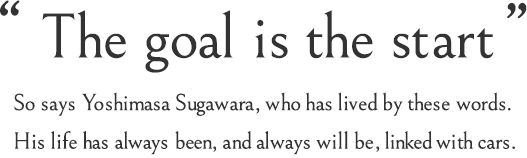

"My dad was a hard worker. He had a very disciplined attitude to work, which I witnessed at his side ever since I was little, so working hard always came naturally to me. My love of cars and bikes was also influenced by my father.”Ever since he can remember, he has been around cars and motorcycles, and while still in high school he was serious enough to acquire five driver's licenses: a light vehicle license, a small four-wheeler license, a motorcycle license, three-wheeler license, and a regular license. He went to school by car or motorcycle, and also made runs from Otaru to Hakodate. When his father barred him from taking long rides, he used a shovel to create his own off-road course on the grounds of the Otaru University of Commerce.

"I guess it’s in the blood."That’s what Sugawara mutters. His oldest son, Yoshiharu, is an industrial designer and the driving force behind GK Dynamics. His second son, Teruhito, is a driver who races Hino trucks in the Dakar Rally, just like his father. Both the hardworking drive and the passion for vehicles that Sugawara inherited from his own father have been passed down to his two sons.

At university, he joined the automobile club and took part in driving events, workshop competitions, and rallies. In addition to possessing both the driving and maintenance skills required for rally driving—making him a powerful all-in-one competitor—another point of appeal for Sugawara, who came to Tokyo from Hokkaido, was gaining the opportunity to view scenery all over Japan.

"The ideal travel speed for each section is specified, and it can’t be faster or slower than the time I calculate on paper. It’s like I'm following a red dot above my head, but when I stop at an intersection, the red dot just keeps moving forward.”The red point is a fictitious point following the trajectory of his ideal running time, which Sugawara calculates himself. In other words, it’s a product of his imagination, but it still leads Sugawara onwards during rallies.

After graduating from university, he bought a Honda S600 and entered a combined rally sponsored by a car magazine, which was his opportunity to take up circuit racing.

"After open racing at the Funabashi circuit a week before, I took part in a rally at Mount Adatara in Fukushima, before finally racing my car up the side of the slope in a hill climb. I’d thought I do well in the rally because I’d been doing that for a long time at university—but when it was over, I’d placed third in the circuit, sixth in the rally, and second in the hill climb.”The following year, Sugawara would compete in a professional hill climbing race: the Nikkan Sports Junior Champion Car Race.

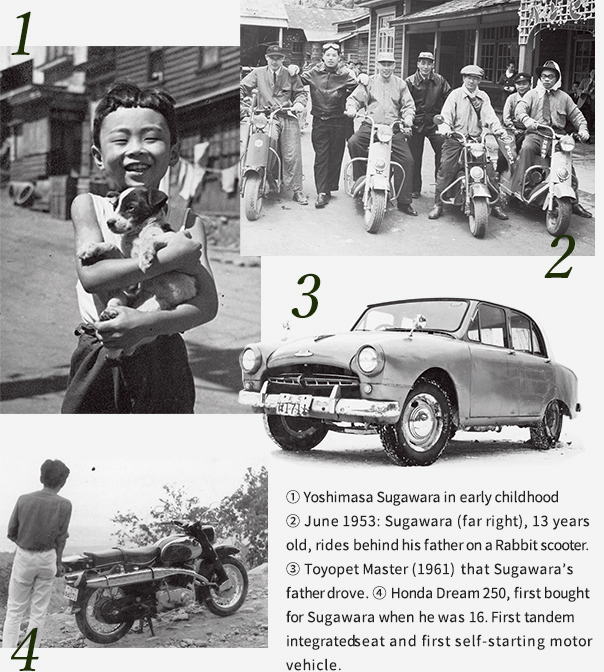

“At first, I tried it in my S600. Tetsu Ikuzawa and Tojiro Ukiya were also competing, although in a different class. The engine was tuned by Yoshimura, who had just arrived in Tokyo, and Yoshimura's father looked after it ever since.”Starting the following year, Sugawara replaced his vehicle with a Mini Cooper S and competed in races on the Suzuka, Funabashi, and Fuji courses in an attempt to earn his credentials as an all-Japan racing driver. In addition to always placing highly and scoring many wins, in light of his goal of outstripping the top-ranked drivers, Sugawara's races appealed to many racing fans.

"Because I always drove along gravel roads and snowy roads in Hokkaido, I’m used to the sensation of side slipping. Humans tend to have a sharp sense of forward and back, but they guard themselves less in the left and right directions.”He felt the limits of his tires, and tested those limits as he powered around corners. That was the strength and speed of Sugawara.

However, before development of his racing team was backed up by financial muscle, Sugawara, who was not a professional racer, faced a succession of hardships. Sugawara placed second in the All-Japan drivers' championships in the T1 class for three consecutive years ('67–'69), failing to beat Toyota-backed racing team.

"Aiming to beat the Toyota factory team, I took on a role as deputy chairman of a private group called the Zero Fighter Car Club and I really tried my hardest. I stripped away some paint to reduce body weight, but the Toyota factory team used a special lightweight body. I was no match for them.”Despite these words, it was only Toyota whom Sugawara was unable to defeat—he consistently ranked ahead of other factory-backed teams, demonstrating the power and significance of private teams. However, as race organizers handed down decisions in favor of factory-backed teams, Sugawara began to distance himself from circuit racing.

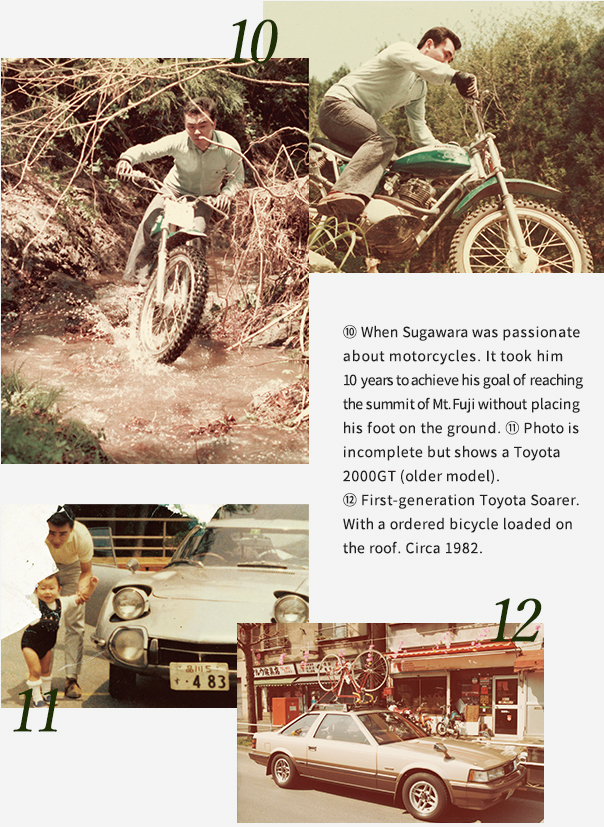

Having moved away from cars, Sugawara became a biker again, and created the “Team Lone Wolf & Cub” club with Tetsu Ikuzawa, Toshinori Asaga, and others. While enjoying motocross, touring, and camping with his friends, Sugawara took on a new challenge. This was reaching the summit of Mt. Fuji by motorcycle.

"I tried various routes and all kinds of bikes. I tried the Honda DAX (ST series). But it didn’t count unless I was riding the entire time. If my foot even touched the ground, it didn’t count. I finally succeeded in my 10th year of trying.”The oxygen was thin and the road surface was uneven due to volcanic ash, but if I stopped the bike even once, it was over. It was difficult to take those hairpin curves without slowing down on the turn.

“At that time I learned of the Paris–Dakar rally, and I wanted to enter. My conquering of Mount Fuji had given me momentum, and when I finally entered Paris–Dakar for the first time, I believed in myself as a man who’d ascended Mount Fuji.”Three years before climbing to Fuji’s summit, Sugawara raced a convoy of three Honda Acty light trucks from Karachi in Pakistan to Lisbon in Portugal. Sugawara was involved from route selection and itinerary planning of the four-month journey of 20,000 kilometers through 14 countries, including areas that are dangerous to traverse these days. He experienced the joys and difficulties of encountering different cultures and crossing deserts, wilderness, and national borders.

He also accompanied Hiroko Hori’s team in crossing the Sahara Desert as a photographer, operating a support vehicle. Approximately 800 kilometers of the non-refueling section that Sugawara traversed at this time overlapped with the Paris–Dakar Rally route, and traveling this route inspired him to turn his dream of entering the Paris–Dakar Rally a reality.

"I thought I could do it. My climbing Mount Fuji, my traveling from Karachi to Lisbon, my crossing the Sahara—these all led me to the Paris–Dakar Rally. But I didn't have enough money to enter in a four-wheeled category, so I took part on a motorcycle."

His first Paris–Dakar Rally could be described as a struggle for Sugawara. “It was exhausting because I didn’t have a firm grasp of the regulations and I didn’t understand French. I was able to write my own competitor number “36” on the tank, working from the pronunciation “trente-six,” but I missed the announcements because I didn’t understand the language.

"I decided to do it for 10 years. That’s how long it would take to race convincingly in the Paris–Dakar."He competed in the motorcycle class the following year, but was forced to retire again. On his 3rd attempt, with the backing of Mitsubishi Motors he took part in the four-wheeler class in a Pajero as a navigator but was also forced to retire. In his 4th challenge, in which he took part as a driver, Sugawara finished his run to Dakar in excellent form, placing 33rd overall and 5th in the marathon class.

In his 10th year, Sugawara was contacted by Hino Motors, which had only started to take part in the Paris–Dakar the previous year, and he entered the race in a truck.

“It was exactly 10 years. This would mean I’d entered the Rally in 3 divisions—motorcycles, four wheelers, and trucks—and I was actually thinking of quitting the tournament after this last time. I thought racing a truck sounded fun."Sugawara, who placed second in the prologue event, demonstrated spectacular performance in the Special Stage (SS) event, placing first by dominating mighty racing trucks in the SS in the mountains near South Africa. In the process, Sugawara discovered new meaning in the Paris–Dakar, while Hino Motors also sought Sugawara’s experience and skills.

27 years later. Although the team has been variously factory-backed or privately entered, depending on economic conditions, etc., Sugawara and Hino joined forces to race the Paris–Dakar. Even when the event’s setting shifted from Africa to South America, nothing changed and the Hino team’s Sugawara became notorious as the "Little Monster," reflecting his position as a unique driver and an indispensable presence in the Dakar Rally.

"I've made it this far thanks to my family and my sponsors. I’m truly grateful."After saying this, Sugawara went on, "I’ve been able to come this far because I suppose I’m the naturally cautious, prudent type."

In 2019, at the age of 77, Sugawara holds the record with 36 consecutive entries in the Dakar Rally. In addition, Sugawara also takes part in Rally Mongolia as well as Japanese rallies such as Hokkaido 4 Days and Tour de Blue Island as training events, and even now participates in motorcycle and car racing events, never losing his positive attitude.

© 2017 Resonance Inc. All Rights Reserved.